Wandering Through Hue’s Hidden Corners: A Street-Level Adventure

You know what’s wild? How much soul you find just walking—no plan, no map, just you and the quiet hum of local life. In Hue, Vietnam, the real magic isn’t in guidebooks. It’s in the alleyways where motorbikes sneak past breakfast stalls, in neighborhoods where history whispers from weathered walls. I didn’t come for palaces—I came for pulse. And what I found? A city alive in every cracked sidewalk and corner café. This is not a journey of grand monuments or curated itineraries, but of human rhythms, fleeting glances, and the warmth of everyday existence. Here, travel becomes not about seeing, but about feeling.

The Heartbeat of Hue: Why City Blocks Tell the Real Story

Hue moves to a rhythm few tourists truly hear. Beyond the grand gates of the Imperial City and the polished brochures lies a network of residential lanes where life unfolds in real time. These neighborhoods are not preserved for display—they live, breathe, and evolve with each passing day. Here, the morning begins not with alarms, but with the sizzle of pork in clay pots, the clink of porcelain bowls, and the soft chime of bicycle bells weaving through narrow streets. It is in these unassuming corners that the soul of Hue reveals itself—not through grand gestures, but through routine, repetition, and resilience.

Walking through a typical district like Gia Hoi or An Cuu, one notices how tradition and modernity coexist without conflict. A grandmother in a conical hat sweeps her tiled porch while her grandson scrolls through a smartphone on the step beside her. A tailor operates a pedal-powered sewing machine under a fading awning, just as his father did decades ago, yet his daughter takes orders via a social media page. These quiet juxtapositions are not signs of cultural erosion, but of adaptation—of a city that honors its past while embracing the present on its own terms.

The sensory tapestry of daily life is rich and layered. The scent of bún bò Huế, the city’s famous spicy beef noodle soup, rises from street kiosks before sunrise, mingling with the earthy aroma of wet pavement after a morning shower. Laundry flutters between buildings like colorful flags, and potted marigolds bloom on window ledges. Children pedal to school in crisp white uniforms, their backpacks bouncing with each turn of the wheel. Elders gather at corner cafés, sipping slow-drip coffee from tiny glasses, their conversations rising and falling like a familiar melody. These moments are not staged—they are lived.

And it is precisely this authenticity that makes street-level exploration so transformative. Unlike structured tours, which often prioritize efficiency over intimacy, wandering allows for serendipity. You don’t just see Hue—you experience its breath, its pace, its quiet pride. There’s a deeper connection formed when you share a nod with a street vendor, or pause to watch a family prepare offerings for a home altar. These are not tourist transactions; they are human acknowledgments. In a world where travel often feels rushed and performative, Hue reminds us that the most meaningful journeys are the ones that unfold slowly, block by block.

The Imperial City’s Shadow: Life on the Fringe of History

The Imperial Citadel of Hue, a UNESCO World Heritage site, stands as a monumental testament to Vietnam’s royal past. Its towering walls and ornate gates draw thousands each year, yet just beyond its perimeter, life continues in quiet defiance of spectacle. In the shadow of history, ordinary residents go about their days—cooking, trading, repairing, and raising families—unfazed by the echoes of emperors and dynasties. This is where the past and present intersect not as a performance, but as a lived reality.

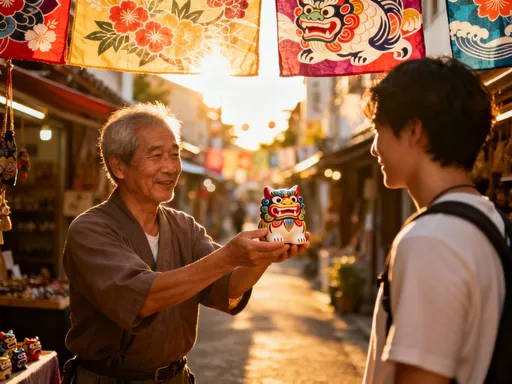

Along the narrow lanes branching from the Citadel’s outer walls, small family businesses thrive. Shops selling handwoven conical hats—nón lá—display their wares beneath faded signs. The craftsmanship is meticulous: each hat is shaped from palm leaves, stitched with precision, and often adorned with delicate poems or paintings visible only when held up to the light. Nearby, incense makers roll fragrant sticks by hand, their fingers moving with practiced ease. These artisans don’t cater solely to tourists; many of their customers are locals who use the products for daily rituals and ancestral worship.

Tourism has undeniably influenced these areas, but it has not overtaken them. Unlike cities where heritage zones become sanitized for visitors, Hue’s surrounding neighborhoods retain their authenticity. You’ll find no souvenir kiosks selling mass-produced trinkets on every corner. Instead, commerce remains personal and purposeful. A woman selling rice cakes from a wooden cart knows her regulars by name. A tailor adjusts a school uniform with care, measuring not just the child but the family’s needs. The presence of tourists is acknowledged, but not catered to at the expense of local life.

Yet, the balance between preservation and progress is delicate. Some sections of the Citadel have been meticulously restored, while others remain in partial ruin—a reminder of war and time. Nearby, new concrete homes rise beside ancestral houses with wooden beams and tiled roofs. This urban evolution is not without tension, but it reflects a city that refuses to be frozen in history. Residents do not live in a museum; they inhabit a dynamic landscape where memory and modernity coexist. Walking these streets, one gains a deeper appreciation for how heritage is not just preserved in stone, but carried forward in daily practice.

West Bank Vibes: Crossing the Perfume River to Authenticity

While most visitors linger on the eastern bank of the Perfume River, drawn to the Imperial City and bustling markets, the western side offers a different kind of beauty—one defined by stillness, simplicity, and residential calm. To cross the river is to step into a quieter rhythm of life. Whether by the pedestrian footbridge near Trường Tiền or aboard a slow-pedaling cyclo, the journey itself becomes a transition from spectacle to substance.

The west bank, encompassing areas like Kim Long and Thủy Xuân, feels untouched by the pressures of tourism. Morning here begins with soft light filtering through frangipani trees, illuminating rows of low houses with open gates and flower-filled courtyards. Laundry hangs above potted herbs, and roosters crow from hidden yards. The air carries the scent of damp earth and simmering broth. There are no guided groups, no souvenir carts—just the unhurried pace of people tending to their homes, their gardens, their routines.

Markets on this side of the river are smaller and more intimate—patchwork affairs where vendors sell fresh vegetables, river fish, and handmade tofu from wooden trays. Transactions are quick, familiar, often conducted with a smile rather than words. A grandmother in a faded apron offers a sample of ripe mango; a fishmonger wraps your purchase in banana leaves. These are not performances for visitors—they are the real economy of daily life.

Street art, too, finds a quiet voice here. On the side of an old brick wall, a mural of a phoenix rises in faded paint—perhaps a nod to Hue’s royal legacy. Elsewhere, a child’s chalk drawing of a dragon decorates a sidewalk. These spontaneous expressions add texture to the neighborhood without disrupting its serenity. Unlike curated art districts in larger cities, this creativity feels organic, unforced.

For the wandering traveler, the west bank is a gift. It invites slowness. A morning walk along its lanes can stretch into hours, not because there’s much to “see,” but because there’s much to absorb. The absence of crowds allows for presence—of mind, of spirit. You begin to notice the way light falls across a courtyard, the sound of a distant radio playing traditional ca trù music, the way an old man feeds breadcrumbs to sparrows. These are the moments that linger, not because they are dramatic, but because they are true.

Local Eats Off the Radar: Where Flavor Lives in Plain Sight

In Hue, food is not just sustenance—it is identity. The city’s cuisine, recognized by UNESCO as part of Vietnam’s intangible cultural heritage, is bold, aromatic, and deeply rooted in ritual. While restaurants near tourist zones offer polished versions of local dishes, the most authentic flavors are found in unmarked stalls, sidewalk kitchens, and family-run shops tucked into quiet alleys. Here, food is not presented—it is shared.

Take bánh khoái, the crispy rice pancake stuffed with shrimp, bean sprouts, and pork. It’s not served on white tablecloths, but on tiny plastic stools under a tarpaulin roof. The cook, often a woman in her 50s with practiced hands, pours the batter onto a hot skillet, flips it with a flick of the wrist, and wraps it in lettuce leaves with fresh herbs. You eat it with your hands, dipping it into a tangy, slightly sweet sauce that varies from vendor to vendor—each claiming theirs is the original.

Then there’s cơm hến, a humble dish of rice topped with tiny river clams, pork rinds, peanuts, and a medley of herbs. It looks simple, but its flavor is complex—earthy, salty, crunchy, fresh. It’s often sold by elderly women who have been preparing it for decades, their wooden carts a familiar fixture on the same corner each morning. To eat cơm hến is to taste the river, the soil, and the patience of generations.

Herbal drinks, too, are a staple. Bright green sữa đậu xanh (mung bean milk), deep purple nước sâm (a cooling herbal infusion), and yellow nước mía (sugarcane juice) are poured from large glass jars into plastic cups. They are sold not for Instagram appeal, but for refreshment—especially welcome under Hue’s humid sun.

How do you find these places? Look for clusters of locals, not English menus. Watch where motorbikes park briefly—frequent stops often mean good food. Follow the smell of charred meat or simmering broth. And don’t be afraid to point and smile; most vendors are happy to serve a curious foreigner. Hygiene is generally sound—many cooks use gloves, cover their food, and wash utensils frequently. But it’s wise to carry hand sanitizer and stick to bottled water. The rewards far outweigh the risks: every bite is a story, a tradition, a connection.

The Art of Getting Lost: Navigating Without a Map

In a world of GPS and curated itineraries, getting lost feels like a radical act. In Hue, it is also one of the safest and most rewarding. The city is compact, walkable, and remarkably safe for solo travelers, especially women. Crime rates are low, and residents are accustomed to foreigners—not with the commercial eagerness of major tourist hubs, but with quiet hospitality.

The art of wandering begins with letting go. Start at a familiar point—Đông Ba Market, the foot of Trường Tiền Bridge, or a quiet alley near a pagoda. Then, simply walk. Don’t consult your phone. Don’t search for landmarks. Let your senses guide you. Follow the smell of grilled meat. Turn toward the sound of laughter. Pause when you see an old man tending bonsai trees on his porch. These are not detours—they are the journey.

Carry small bills—20,000 or 50,000 VND notes—for street food and small purchases. Greet shop owners with a simple “Xin chào” (hello) and a smile. Most will respond warmly, even if they don’t speak English. Some may invite you to sit, offer tea, or show you family photos. These moments are not transactions; they are gestures of kindness.

Getting lost doesn’t mean being careless. Stay aware of your surroundings, especially during evening hours, though even then, the streets remain peaceful. Stick to well-lit areas, and trust your instincts. But also trust the city. Hue does not feel threatening. It feels open—inviting even the most hesitant traveler to explore without fear.

And when you do find your way back—perhaps retracing your steps past a familiar noodle stall or a blue-painted gate—you realize something: you weren’t lost at all. You were found. Found in the rhythm of a place, in the quiet confidence that you belong, even if only for a moment.

Moments That Stick: Human Encounters in Passing

It’s not the monuments that stay with you. It’s the grandmother frying spring rolls in a blackened pan, who offers you one with a toothless grin. It’s the bike repairman who stops his work to draw you a map in the dirt with a stick. It’s the children on their way home from school who shout “Hello!” not for attention, but for connection, their faces lit with genuine delight.

These brief encounters are the invisible threads that weave a place into your memory. They are fleeting, unscripted, and profoundly human. In Hue, where life unfolds at street level, these moments are not rare—they are routine. A woman selling lotus tea nods as you pass. A tailor waves from his doorway. An old man playing a two-stringed đàn nhị looks up and smiles mid-melody.

What makes these interactions so powerful is their lack of performance. There is no expectation of a tip, no script to follow. They happen because someone saw you, acknowledged you, and chose to share a fragment of their day. In a world where travel can feel transactional, these exchanges restore faith in simple kindness.

Respect is key. Avoid staring. Don’t take photos without permission. A smile, a nod, a quiet “cảm ơn” (thank you)—these small gestures go far. And when a conversation begins, listen more than you speak. Let the moment unfold naturally. These are not photo ops; they are human connections.

Why This Kind of Travel Changes You

Walking through Hue’s hidden corners does more than reveal a city—it changes the traveler. It fosters empathy, not through grand revelations, but through quiet observation. You begin to see beyond the surface, to appreciate the dignity in daily labor, the beauty in routine, the strength in simplicity. You learn to move slowly, to notice, to be present.

This kind of travel is not about collecting sights, but about cultivating sensation. It’s the warmth of a coffee cup in your hands at dawn, the sound of rain on a tin roof, the smell of incense after a storm. It’s the understanding that every city has layers—not just of history, but of life.

Hue teaches humility. It reminds us that we are guests, not owners. We do not come to conquer or consume, but to witness and appreciate. And in doing so, we return home not with souvenirs, but with shifts in perspective—subtle, lasting, profound.

So let go of the map. Walk first. Plan later. Let the city reveal itself, one block at a time. Because the truest adventures are not found in guidebooks, but in the quiet hum of life as it’s lived. In Hue, that hum is a song—and if you listen closely, it just might change your rhythm too.